Pride and Prejudices and “Totalausfall”

Why Germany’s “Coming-to-Terms” with its Nazi past has not only failed but backfired.

Since the beginning of Israel’s genocide in Gaza, Germany has shocked much of the world by its callous response. In essence and with far too few exceptions, the German elites – in government, media, and culture as well – have chosen to support Israel’s assault and, at home, to aggressively suppress any criticism of it, habitually by smearing it as “antisemitism.”

The evidence of this pattern – which has been called an “absurd, clumsy,” and “racist…taboo” in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz – is overwhelming, as you would expect with something so collective and conformist. There are, of course, facts such as that the German government has multiplied its arms exports to Israel during the Gaza Genocide and tried to intervene on the side of Tel Aviv when South Africa brought its – by now essentially successful – case against Israel. Recent examples in the realm of culture (and politics, too) include the shameful targeting of Yuval Abraham and Basel Adra, critical filmmakers from Israel, one Jewish, one Palestinian, after they dared speak up for peace and justice at the Berlinale.

In view of the sheer size of the phenomenon, it would be futile to try to compose a complete catalogue of exhibits of the German elites’ current failure to respond adequately – intellectually and ethically – to the Gaza Genocide. But take, for instance, Volker Beck, an influential politician from the Green party, head of the Deutsch-Israelische Gesellschaft and an academic instructor in matters of religion and politics at Bochum University, a major institution.

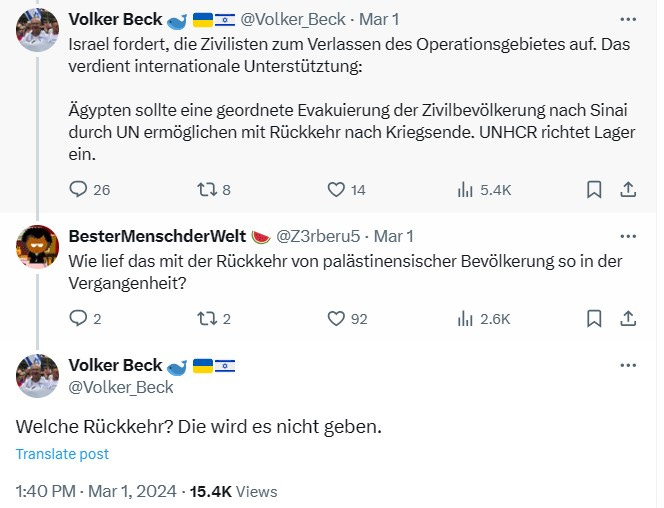

At the beginning of March, Beck tweeted that Israel’s call for Palestinian civilians to leave the “operation area” – that is, by then mostly the southern corner of Gaza into which most of them had been brutally displaced already – deserves international support. He felt that Egypt should facilitate an “evacuation” of Palestinian civilians into the Sinai, that is, a desert, of course. He generously added that the UNHCR (not UNRWA, take note!) could build the requisite camps. He also wrote about a “return [presumably to Gaza] after the end of the war.” Yet when quickly challenged about the fact that Israel’s historical record of letting “evacuated” (that is, really, ethnically cleansed and expelled) Palestinians return anywhere is abysmal, he promptly shot back: “What return? That will not happen.” (See screenshot below.)

Beck, it is true, later tried to recast his clear if inconsistent statements as somehow referring only to failed (really, prevented) returns before the current genocide. Curiously, this almost comically self-damaging “defense” seems to show that he believes that blithely dismissing the Palestinian right of return between 1948 and early October 2023 is less problematic than his initial message. (He also reacted with intriguing alacrity to my public inquiry about his tweet, hinting at legal consequences in what seemed to be an attempt at a bit of threatened lawfare to stifle criticism.)

But the key point remains that Beck cannot – or will not? – even spot an ethical issue with lending his public support to an “evacuation” into a desert that will, judging by all historical precedent as well as by Israel’s current actions and even explicit statements, be a cover for ethnic cleansing facilitated by genocide. He may or may not understand the implications of his statements made in a context that is, however, obvious. But that is irrelevant. He is, unfortunately, typical for much of the German “elite” attitude – and yes, it is rather homogenous, unfortunately – during the ongoing Gaza Genocide.

Yet this is not, unfortunately, a problem restricted to elites. Even a quick perusal of German Twitter/X will quickly impress you with the quantity of voices of brutality among “ordinary” Germans. From those gratuitously slandering the Palestinian victims of a genocide as “barbarians” who have, in essence, brought it on themselves to those Germans who publicly laugh off Palestinian death and suffering as “Pallywood” (“Palestine” plus “Hollywood”… Get it?) that is, fake.

It is almost as if there were a vicarious sadism about in German society, a genuine pleasure in mocking and demeaning the Palestinian victims, different in scale but not fundamentally from the obvious sadism displayed by many Israeli perpetrators in inflicting pain and death.

It is tempting to refer to racism, which is certainly very real in Germany, as the cause of the callousness as well as the active – if verbal – participation in Israeli sadism. In general, many Germans certainly see Israelis as fellow “whites” and Palestinians as “brown” others, which is a pre-condition at least for the manner in which they react to the former genociding the latter. And, as far as religion is concerned, contemporary Germans have, of course, learned to reserve xenophobic contempt for Islam alone (and mostly do not understand the real religious complexity of Palestinian society either, by the way). Yet stopping with racism would fall far short of a useful explanation. For two reasons: First, racism is generic and protean, and it amalgamates easily with other forms of resentment and viciousness. While it can take many forms, the specific shape racism actually takes depends on those amalgamations.

Second – and perhaps even more importantly in this context – it is not enough to have a non-naïve theory about the causes of the ruthless indifference, cold contempt, and sheer malice that are coming through in Germany’s reaction to the Gaza Genocide. It is more urgent to understand why this spectrum of reactions ranging from malevolent indifference to venomous animosity is not only tolerated but sets the tone and determines actions (such as arms sales). The key problem is not, in other words, that there are aggressively ignorant, callous, or vile responses to the Gaza Genocide in Germany, but that they are widespread, dominant, and, literally, shame-less as well as free of social “cost,” shared between much of “above” and “below” and backed up by the media.

Beyond racism, this national moral and intellectual failure, which Germans will come to regret (once again), has rested on three ideological pillars: First, the claim that unconditional support for Israel – not “only” Jews, but specifically Israel, while the two notions are, of course, relentlessly conflated – is German “Staatsräson” (reason of state), a purpose so baked into Germany’s post-World War II existence that it cannot be questioned, even when standing by Israel leads to complicity in apartheid, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. It is, ironically, a new edition of that famous German “Nibelungentreue” – a loyalty taken to such mindless extremes that all other moral values and claims are suppressed, and proudly so.

Second, the presumption that Germans, with their rich national history as perpetrators of both antisemitism and genocide, know best how to recognize those two phenomena and also – this is the key part – of how to not recognize them, or to be precise, to pronounce on their absence. In this bizarre logic, Germans have a special superpower, founded, in effect, on their own history of mass crimes, of absolving Israel from perfectly plausible, even compelling accusations of genocide.

This conceit has been displayed most succinctly by Matthew Karnitschnig, an American-Austrian journalist who denied that there was a genocide in Gaza with direct reference to that putative special expertise (see screenshot below). There cannot be a genocide, he intuited, when Germans, with their special expertise, choose not to see one.

Bad luck, Palestinians: Your suffering doesn’t pass the German Genocide Purity Test. Because whatever you may experience and feel there, on the ground, under starvation blockade, bombs, and sniping, Germans know better. Because they have done genocide, unlike you, but like the Israelis killing you right now.

And third, there is a widespread and largely, again, unquestioned belief that Germany has not only learned from its dark past but has – not at all the same thing – learned the right lessons. Germans almost never even ask the obvious question if they could have made mistakes in the very process of learning. Scour German self-questioning and its shape is, in essence and most of the time, “have we done enough of the right thing?” not “have we, actually, done the right thing?”

That may be an astounding attitude, once you think about it, but there it is. A purported effort to face one’s worst mistakes, indeed crimes, does not, actually, come with much humility. Instead, there is a self-assured – if superficially tormented – sense of being the best again: the former “world champions of export” tend to see themselves as “world champions of coming to terms with the past,” too.

How do we explain this grotesque picture?

Let’s get a common and traditional assumption – and mistake – out of the way first: It may seem that German society is, in essence, driven insane by persistent feelings of guilt. On that assumption, the puzzle is how to explain its deeply uncompassionate and even brutal response to the suffering of the Palestinians: How can those racked with guilt over the genocidal crimes of their forebears find it so easy to not only abandon another group of victims to a genocidal attack, but also help the perpetrators?

Attempts to answer that question – and I have tried myself in this vein – usually turn on some notion of perverse over-compensation (let’s call it the “guilt-and-perverse-response theory”). Many Germans, so this argument goes, use their demonstrative loyalty to Israel – even and especially when the latter commits atrocious crimes, including genocide – to assuage that old sense of guilt. In that logic, the Palestinian victims either do not matter – that is, they are, in effect, dehumanized by reducing them to mere objects of Germans’ emotional needs – or, in a more pro-active variant of the mechanism, their suffering even serves to validate the German self-unburdening operation: The Palestinian victims of Israeli violence, whether apartheid or genocide, become a kind of psychological human sacrifice to appease the demons of German souls tormented by what earlier Germans have done. The horrifying irony of this “displacing colonialism of memory management” (as I have called this mechanism elsewhere) is, of course, that a perverted attempt to atone for one immense crime is leading to obstinate, if largely indirect participation in or at least justification of yet another one.

I still believe that something on the lines sketched above is happening. Yet explanations of the “guilt-and-perverse-response” type are clearly insufficient to capture the resilience and aggression displayed by Germany. If guilt were the only or even central factor in play, then it could explain an initial confusion over an event such as the Gaza Genocide.

But the pattern would have to break down under the stress of the first genocide in human history that is, in essence, live streamed as well as prolonged. Yet Germany has stayed the course into the sixth month of the slaughter now. Superficial gestures, such as joining the USA in its “Gaza harbor” propaganda and distraction operation, make no difference to this fact. Indeed, they only underline it.

We need something harder and less humble than guilt – however much perverted – to explain the ferocity with which many Germans have doubled down on their commitment to Israel come-what-may. Guilt is, after all, a state that is inherently open to genuine self-questioning. The type of self-questioning, that is, that does not only serve rhetorical ingratiation purposes but leads to radical changes of action. Yet that is not at all what we see in this case. Instead, we see a single-mindedness, obstinacy, and collective intolerance of dissent that is beginning to be reminiscent of earlier, more openly authoritarian versions of German society.

The virtually total failure of Germany’s intellectual and moral moorings (this German “Totalausfall,” to use a German term) in face of the Gaza Genocide calls for a fundamental rethinking of the what the German coming-to-terms-with-the-past has actually been. Not what its proponents, adherents, and admirers have said about it or even honestly intended. The first step we need to take for such a truly critical reassessment is to understand that its motivation was shame, not guilt, and that – more importantly – shame and guilt can be connected, but they do not have to be, and they are not at all the same.

For at the core of Germany’s failure is not misdirected guilt, but the shame that comes from massively injured pride. In reality, Germany has been engaged in a trade: Public atonement for the Holocaust against relief from the historic and self-inflicted humiliation of belonging to a top genocider state that was also defeated in not one but two World Wars.

That is why the result of this effort is so callous, indeed arrogant. Whatever honest intentions that certainly went into it as well, Germany’s “coming-to-terms” with its past could only become a national consensus project by assuaging a self-wounded national ego. In other words, the project’s real purpose was not (or, perhaps, did not remain) to make Germany honest, but to make Germany proud again. And by now, its elites are so proud, so self-confident, so, frankly, puffed-up with a humble-bragging sense of superiority that they show no qualms even about tolerating and supporting massive atrocities, including genocide. As long, that is, as siding with the perpetrators and victors promises to help confirm that Germany is now a recognized “great power” in the Western value “garden.” The irony of this is, of course, that pride comes before a fall, another lesson from history Germany seems unable to absorb: Germans will soon have to open a fresh chapter of “coming-to-terms,” namely with their national failure over the Gaza Genocide.

Excellent and insightful analysis. I wonder if we can apply Shlomo Sands’ insights about contemporary French society to Germany. That current Islamophobia, of which fanatical support of Israel’s actions is an expression, has replaced anti-semitism as the hatred of the ‘ other’. That current exponents of Islamophobia would be right at home with the anti-semites of the mid-twentieth century. The only difference is the target of the hatred - Muslims in the current case and Jews 80 years ago. In any case it means Germany has learned nothing, just like the US where previous extreme hatred of people of African descent has been replaced by a deep seated hatred and unacknowledged hatred of Arabs and Muslims.

I majored in German and lived for a year in Austria. It struck me very much then that 1) Germans had done a better job than Austrians in coming to grips with their Nazi past, but that (2) that atonement was imperfect. I noticed Germans and Austrians were very racist against Turks and other people from majority Muslim countries. Some of our fellow students asked us why Americans were prejudiced against Blacks. In response, a smart undergrad asked if the girl who was asking this question would ever go out with a Turk. Never! Was the response. And I think the Austrian girl couldn’t see her inconsistency. This was in the ‘80s, btw.